Roger Landault

Born in 1919 in post-war Paris, Roger Landault was far more than just a designer—he was a true alchemist of form and material, an artist who captured the spirit of his time and transformed it into everyday objects of beauty. Trained in the applied arts from his youth, he took on the role of artistic director at Studium-Louvre in 1945, a hub where the contours of the modern world were being sketched. It was there, in the heart of this creative crucible, that his talent flourished, earning him the first prize at the Concours du Meuble de France. This distinction opened the doors to major publishers, including ABC, marking the beginning of a career as prolific as it was inspired.

His creative journey reads like a novel, with each decade bringing its own transformations. In the 1950s, as France rebuilt itself, Landault designed furniture that embodied this spirit of renewal. The Junior collection, simple and functional, met the needs of an era seeking both simplicity and durability. This was followed by Dakar and Rotterdam, solid wood collections that earned him the prestigious Prix René-Gabriel, a recognition of his ability to blend utility with aesthetics. But Landault was never one to rest on his laurels—he explored, he experimented. Sometimes he drew inspiration from the clean lines of Scandinavian design, as seen in Chatelaine and Rio, and other times he dared to be bold, like with the Panama dressing table, whose leather-clad doors added an unexpected touch of refinement.

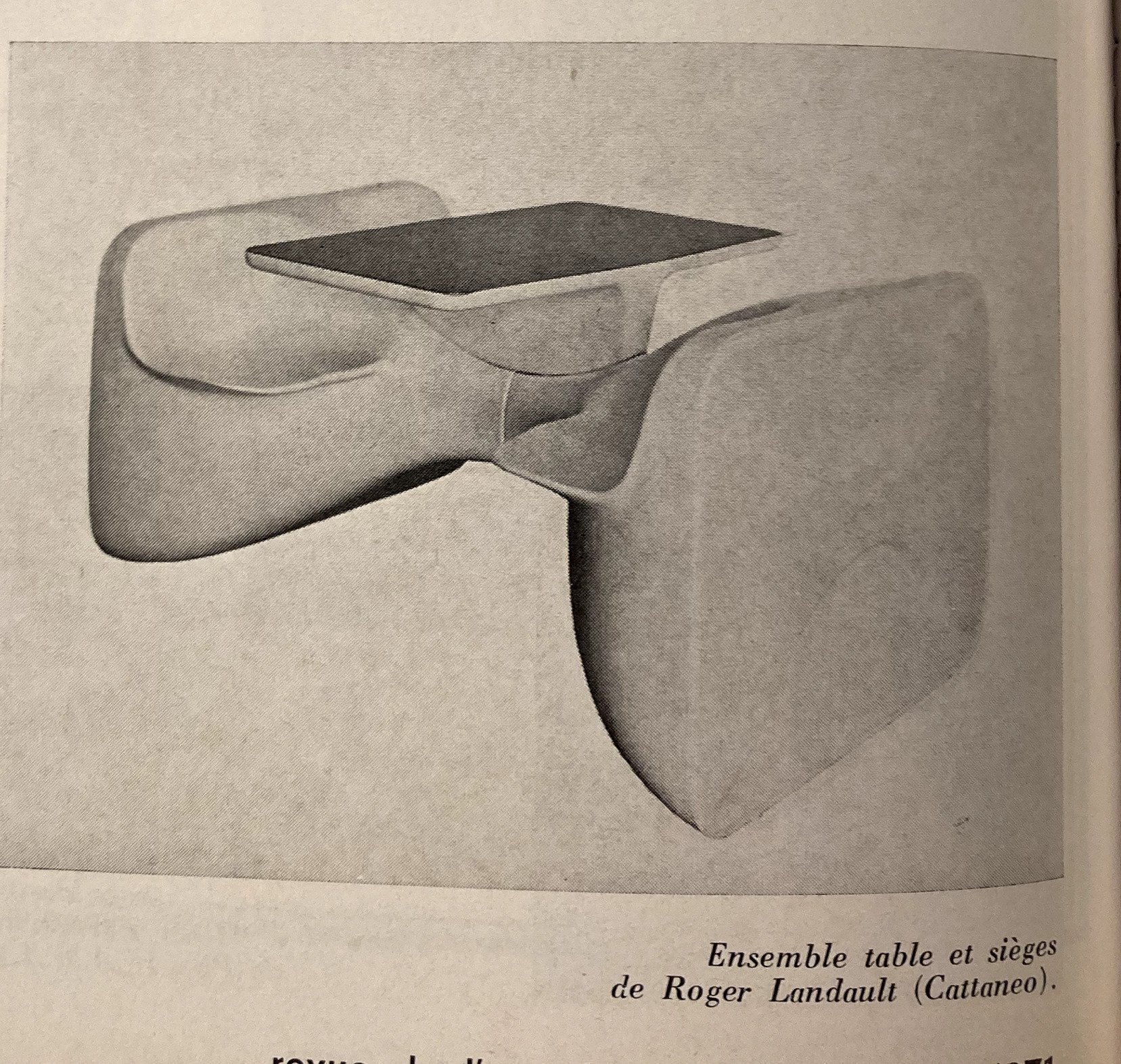

The 1960s and 1970s saw Landault embrace the materials of his time with enthusiasm. For Steiner, he created the Unibloc tables, futuristic ensembles in thermoformed plastic, where integrated benches and fluid lines redefined the art of dining. With Robert Sentou, he designed chairs in oak and wicker, such as the Ellipse model, where the curve of the wood converses with the softness of the cane. And then there was his collaboration with Charles Steiner on the Super-Knoll line, a tribute to organic and functional design, where every detail seemed crafted to fit the gestures of daily life.

Among his creations, certain pieces stand out as quiet icons of their time. The Antony chairs, designed for the Jean Zay University Residence, combine light oak and gray vinyl, a blend of materials that reflects the optimism of a youth on the move. The 6517 chair, published by Bouvier, embodies the understated elegance of post-war French furniture. And what of the Compas armchairs, in oak and bouclé wool, where the geometric rigor of the compass legs meets the enveloping softness of the wool, creating a perfect balance between structure and comfort?

Roger Landault passed away in 1983, leaving behind a body of work that transcends eras. His legacy is not one of a single style, but of a constant quest, an ability to see in every material and technique a new way to beautify the everyday. His creations, both artisanal and industrial, bear the mark of a man who listened to his time in order to elevate it. Each piece he designed tells a story—of a designer who, throughout his life, turned constraints into opportunities and objects into silent poetry